ORIGINAL: The Guardian

Oliver Tickell and Terry Macalister theguardian.com,

12 October 2012

'Carbon negative' cement technology put up for sale when its British developer was declared insolvent

A mystery Australian company has bought the rights to a green technology spun out of Imperial College London that promises to clean up one of the world's most carbon-polluting industries.

The "carbon negative" cement technology was put up for sale when its British developer, Novacem, was declared insolvent this week. The rights have now been sold for a sum believed to be several hundred thousand pounds. About £4-5m had been pumped into the company by investors and other backers.

"We are satisfied that the buyer will be able to take the invention to the next level," said James Money of London-based insolvency practitioners PKF. "They are committed to making this work."

The idea, which involves mixing magnesium oxide with high-purity sand, offers the prospect of turning the cement industry from one that emits 2bn tonnes of CO2 a year – more than 5% of human CO2 emissions – into one that removes CO2 from the atmosphere.

While the sale is good news for the creditors, it is a sad end for one of Britain's most promising green-tech companies, twice listed in the Global Cleantech 100. Novacem began as a spin-off from Imperial College London in 2007, and its investors and other backers include Imperial Innovations, the Royal Society Enterprise Fund, the London Technology Fund and the Carbon Trust. It has also recruited Rio Tinto, Laing O'Rourke and WSP as industrial partners. But it was unable to raise further funds and entered a creditors voluntary liquidation last month.

Novacem founder and chairman Stuart Evans believes the purchase would "make a fortune" for the buyer within a decade.

"Right now, it needs $50-100m in investment but once the technology is established, it will be worth billions. You can just do the arithmetic. It is unfortunatethat even the best of British venture capitalists find it hard to take on an opportunity like this."

TR10: Green Concrete

ORIGINAL: Technology Review

por Taylen Peterson

04/23/2010 13:57

Storing carbon dioxide in cement.

David Bradley

May/June 2010

Oliver Tickell and Terry Macalister theguardian.com,

12 October 2012

'Carbon negative' cement technology put up for sale when its British developer was declared insolvent

A mystery Australian company has bought the rights to a green technology spun out of Imperial College London that promises to clean up one of the world's most carbon-polluting industries.

The "carbon negative" cement technology was put up for sale when its British developer, Novacem, was declared insolvent this week. The rights have now been sold for a sum believed to be several hundred thousand pounds. About £4-5m had been pumped into the company by investors and other backers.

"We are satisfied that the buyer will be able to take the invention to the next level," said James Money of London-based insolvency practitioners PKF. "They are committed to making this work."

The idea, which involves mixing magnesium oxide with high-purity sand, offers the prospect of turning the cement industry from one that emits 2bn tonnes of CO2 a year – more than 5% of human CO2 emissions – into one that removes CO2 from the atmosphere.

While the sale is good news for the creditors, it is a sad end for one of Britain's most promising green-tech companies, twice listed in the Global Cleantech 100. Novacem began as a spin-off from Imperial College London in 2007, and its investors and other backers include Imperial Innovations, the Royal Society Enterprise Fund, the London Technology Fund and the Carbon Trust. It has also recruited Rio Tinto, Laing O'Rourke and WSP as industrial partners. But it was unable to raise further funds and entered a creditors voluntary liquidation last month.

Novacem founder and chairman Stuart Evans believes the purchase would "make a fortune" for the buyer within a decade.

"Right now, it needs $50-100m in investment but once the technology is established, it will be worth billions. You can just do the arithmetic. It is unfortunatethat even the best of British venture capitalists find it hard to take on an opportunity like this."

TR10: Green Concrete

ORIGINAL: Technology Review

por Taylen Peterson

04/23/2010 13:57

Storing carbon dioxide in cement.

David Bradley

May/June 2010

OTHERS WORKING ON GREEN CONCRETE

Kurt Zenz House, MIT

Calera, Los Gatos, CA

Joseph Davidovits, Geopolymer Institute, Saint-Quentin, France

This article is part of an annual list of what we believe are the 10 most important emerging technologies. See the full list here.

|

| Nato Welton Nikolaos Vlasopoulos (Novacem) Green concrete could reduce global carbon emissions that are due to cement production |

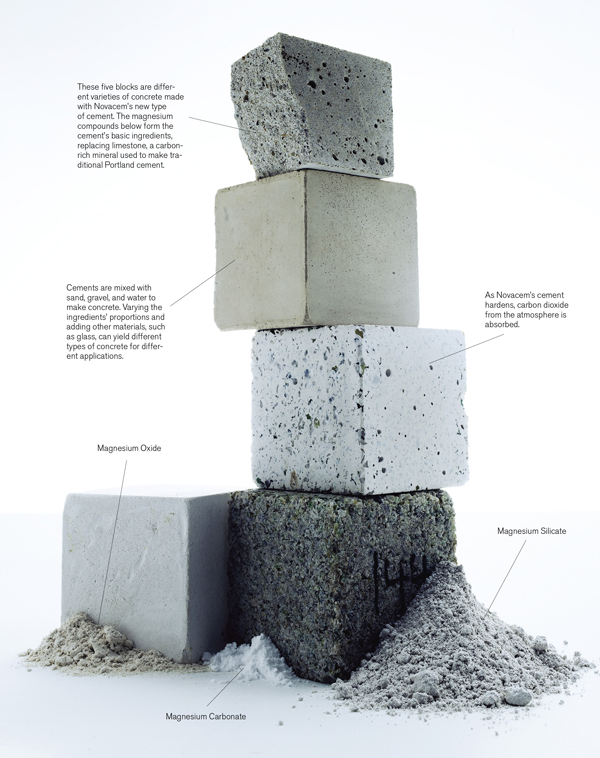

Making cement for concrete involves heating pulverized limestone, clay, and sand to 1,450 °C with a fuel such as coal or natural gas. The process generates a lot of carbon dioxide: making one metric ton of commonly used Portland cement releases 650 to 920 kilograms of it. The 2.8 billion metric tons of cement produced worldwide in 2009 contributed about 5 percent of all carbon dioxide emissions. Nikolaos Vlasopoulos, chief scientist at London-based startup Novacem, is trying to eliminate those emissions with a cement that absorbs more carbon dioxide than is released during its manufacture. It locks away as much as 100 kilograms of the greenhouse gas per ton.

Vlasopoulos discovered the recipe for Novacem's cement as a grad student at Imperial College London. "I was investigating cements produced by mixing magnesium oxides with Portland cement," he says. But when he added water to the magnesium compounds without any Portland in the mix, he found he could still make a solid-setting cement that didn't rely on carbon-rich limestone. And as it hardened, atmospheric carbon dioxide reacted with the magnesium to make carbonates that strengthened the cement while trapping the gas. Novacem is now refining the formula so that the product's mechanical performance will equal that of Portland cement. That work, says Vlasopoulos, should be done "within a year."

Other startups are also trying to reduce cement's carbon footprint, including Calera in Los Gatos, CA, which has received about $50 million in venture investment. However, Calera's cements are currently intended to be additives to Portland cement rather than a replacement like Novacem's, says Franz-Josef Ulm, director of the Concrete Sustainability Hub at MIT. Novacem could thus have the edge in reducing emissions, but all the startups face the challenge of scaling their technology up to industrial levels. Still, Ulm says, this doesn't mean a company must displace billions of tons of Portland cement to be successful; it can begin by exploiting niche areas in specialized construction. If Novacem can produce 500,000 tons a year, Vlasopoulos believes, it can match the price of Portland cement.

Vlasopoulos discovered the recipe for Novacem's cement as a grad student at Imperial College London. "I was investigating cements produced by mixing magnesium oxides with Portland cement," he says. But when he added water to the magnesium compounds without any Portland in the mix, he found he could still make a solid-setting cement that didn't rely on carbon-rich limestone. And as it hardened, atmospheric carbon dioxide reacted with the magnesium to make carbonates that strengthened the cement while trapping the gas. Novacem is now refining the formula so that the product's mechanical performance will equal that of Portland cement. That work, says Vlasopoulos, should be done "within a year."

Other startups are also trying to reduce cement's carbon footprint, including Calera in Los Gatos, CA, which has received about $50 million in venture investment. However, Calera's cements are currently intended to be additives to Portland cement rather than a replacement like Novacem's, says Franz-Josef Ulm, director of the Concrete Sustainability Hub at MIT. Novacem could thus have the edge in reducing emissions, but all the startups face the challenge of scaling their technology up to industrial levels. Still, Ulm says, this doesn't mean a company must displace billions of tons of Portland cement to be successful; it can begin by exploiting niche areas in specialized construction. If Novacem can produce 500,000 tons a year, Vlasopoulos believes, it can match the price of Portland cement.

Video

Even getting that far will be tough. "They are introducing a very new material to a very conservative industry," says Hamlin Jennings, a professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Northwestern University. "There will be questions." Novacem will start trying to persuade the industry by working with Laing O'Rourke, the largest privately owned construction company in the U.K. In 2011, with $1.5 million in cash from the Royal Society and others, Novacem is scheduled to begin building a new pilot plant to make its newly formulated cement.

Comments

Post a Comment