01/28/2014

Building permits are wonderful things: They protect us from slum conditions and scammers, and they make money for our local governments. But permits can also pose a major financial hurdle for independent home builders—and rules are meant to be broken, man.

There's a rich, if somewhat under-the-radar, tradition of architectural loopholes out there, and it ranges from Spain to the backwoods of the United States.

Take this home in Whangapoua, New Zealand, for example. In this coastal community, building code requires all homes to be removable because of erosion issues. The architects—Crosson Clarke Carnachan—took this rule very, very literally: Their beach home is actually built on two wooden skiis, which make it easy to hook up to a tractor and drag to a different location:

Expand

Expand

Then there's Sweden's building code. In 1979, minister of housing Birgit Friggebo changed the law to include an allowance that lets property owners build structures under 90 square feet without building permits.

These tiny shacks even have their own nickname, friggebod, like this one designed by Kenjo:

A similar law, in Finland, allows property owners to build structures under 96 square feet. A few years ago, Finnish designer Robin Falck decided to take advantage of the law by building a tiny home that clocked in just under the limit—despite the fact that it includes a second story sleeping space.

In most of the United States, Falck never would've been able to build his own home for so little money—which is sort of sad. The education of young architects depends on actual building and, these days, most students get that experience through internships. Which is fine, but you could argue that integrating more actual building into the curriculum would benefit everyone involved. A Friggebode allowance in America could make that a whole lot easier.

There are plenty of other ways to get around the law, though. In London, the wealthy owners of protected historical homes have found a way to sidestep the laws protecting their properties from unsightly modern additions: Build under them. These "luxury bunkers" include a four-story addition below a 19th century schoolhouse, and sprawling additions like this one:

Images via.

In 2010, two architects named David Knight and Finn Williams published a book called SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development, which functions as a guide to exploiting planning loopholes.

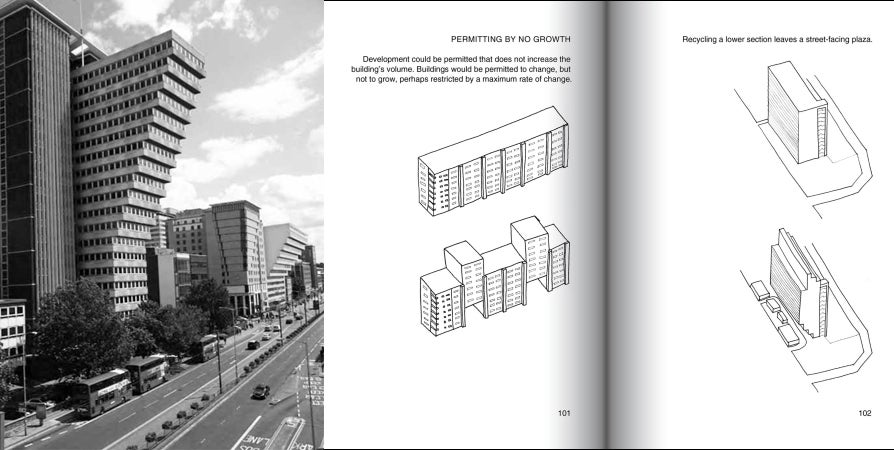

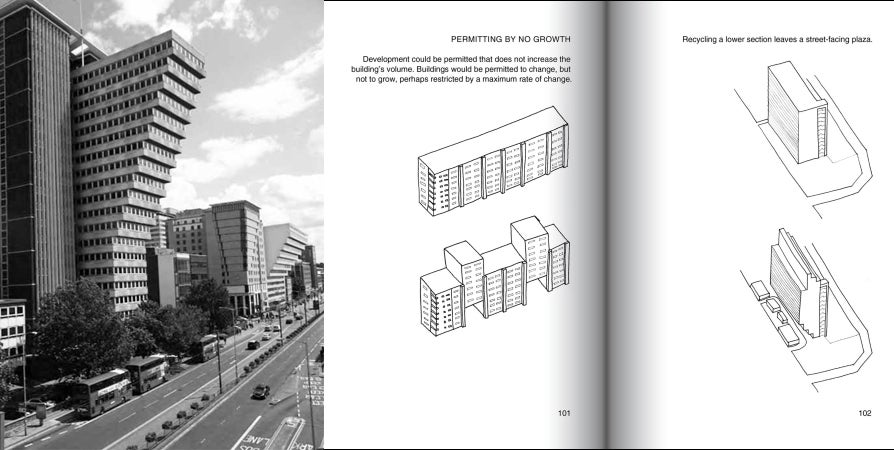

For example, if the law allows additions that don't increase a buildings volume, an architect could subtract pieces here and there, adding them back in unexpected places:

1Expand

1Expand

Then there's Santiago Cirugeda, a Spanish architect and artist who takes a more direct approach. He creates what he calls "urban prescriptions," or ways to subvert building code. For example, one law states that you can obtain a permit for scaffolding only if you "need" to repaint your house. Why not go to town on the facade with a spray can, Cirugeda suggests, as a way around that rule? Here's Cirugeda's tips on how to install rentable apartments on your roof.

In the U.S., the Small House Movement advocates for smaller—much, much smaller—homes, including ones that manage to evade the country's various local building permit restrictions. For example, sometimes a small friggebod-style shack doesn't require permitting. In others, a home on wheels doesn't necessitate a permit. In some remote areas, builders don't need one at all.

At the Tumbleweed Tiny Home Company, you can buy this bad boy for a few—er, many—-monthly payments and tow it around wherever you like:

Images: Tumbleweed Tiny Home Company. Photo by Jack Journey.Related

Of course, there are tons of reasons to subvert (or break) the law when it comes to buildings: Sometimes they are well-meaning, other times, they are deeply misguided and illegal, and it's worth pointing out that building code itself should never be broken. But it's easy to get excited about well-placed loopholes—especially if it means you could build (or help build) your own space.

Over the past century, the average homeowner has moved further and further away from being involved in (or simply aware of) the construction of the home he or she lives in. The same goes for many designers. From balancing a check book to CPR, we're taught all kinds of completely germane life skills in school—why not how to build?

Lead image: Friggebod by Jonas Palmius Formera.

Building permits are wonderful things: They protect us from slum conditions and scammers, and they make money for our local governments. But permits can also pose a major financial hurdle for independent home builders—and rules are meant to be broken, man.

There's a rich, if somewhat under-the-radar, tradition of architectural loopholes out there, and it ranges from Spain to the backwoods of the United States.

Take this home in Whangapoua, New Zealand, for example. In this coastal community, building code requires all homes to be removable because of erosion issues. The architects—Crosson Clarke Carnachan—took this rule very, very literally: Their beach home is actually built on two wooden skiis, which make it easy to hook up to a tractor and drag to a different location:

Expand

Expand

Then there's Sweden's building code. In 1979, minister of housing Birgit Friggebo changed the law to include an allowance that lets property owners build structures under 90 square feet without building permits.

These tiny shacks even have their own nickname, friggebod, like this one designed by Kenjo:

A similar law, in Finland, allows property owners to build structures under 96 square feet. A few years ago, Finnish designer Robin Falck decided to take advantage of the law by building a tiny home that clocked in just under the limit—despite the fact that it includes a second story sleeping space.

In most of the United States, Falck never would've been able to build his own home for so little money—which is sort of sad. The education of young architects depends on actual building and, these days, most students get that experience through internships. Which is fine, but you could argue that integrating more actual building into the curriculum would benefit everyone involved. A Friggebode allowance in America could make that a whole lot easier.

There are plenty of other ways to get around the law, though. In London, the wealthy owners of protected historical homes have found a way to sidestep the laws protecting their properties from unsightly modern additions: Build under them. These "luxury bunkers" include a four-story addition below a 19th century schoolhouse, and sprawling additions like this one:

Images via.

In 2010, two architects named David Knight and Finn Williams published a book called SUB-PLAN: A Guide to Permitted Development, which functions as a guide to exploiting planning loopholes.

For example, if the law allows additions that don't increase a buildings volume, an architect could subtract pieces here and there, adding them back in unexpected places:

1Expand

1ExpandThen there's Santiago Cirugeda, a Spanish architect and artist who takes a more direct approach. He creates what he calls "urban prescriptions," or ways to subvert building code. For example, one law states that you can obtain a permit for scaffolding only if you "need" to repaint your house. Why not go to town on the facade with a spray can, Cirugeda suggests, as a way around that rule? Here's Cirugeda's tips on how to install rentable apartments on your roof.

In the U.S., the Small House Movement advocates for smaller—much, much smaller—homes, including ones that manage to evade the country's various local building permit restrictions. For example, sometimes a small friggebod-style shack doesn't require permitting. In others, a home on wheels doesn't necessitate a permit. In some remote areas, builders don't need one at all.

At the Tumbleweed Tiny Home Company, you can buy this bad boy for a few—er, many—-monthly payments and tow it around wherever you like:

Images: Tumbleweed Tiny Home Company. Photo by Jack Journey.Related

Of course, there are tons of reasons to subvert (or break) the law when it comes to buildings: Sometimes they are well-meaning, other times, they are deeply misguided and illegal, and it's worth pointing out that building code itself should never be broken. But it's easy to get excited about well-placed loopholes—especially if it means you could build (or help build) your own space.

Over the past century, the average homeowner has moved further and further away from being involved in (or simply aware of) the construction of the home he or she lives in. The same goes for many designers. From balancing a check book to CPR, we're taught all kinds of completely germane life skills in school—why not how to build?

Lead image: Friggebod by Jonas Palmius Formera.

Comments

Post a Comment