ORIGINAL: FastCo Exist

Made from organic material that can be turned into fertilizer, this installation will show off a radical, zero-waste building technology that could help chill down sweltering city streets.

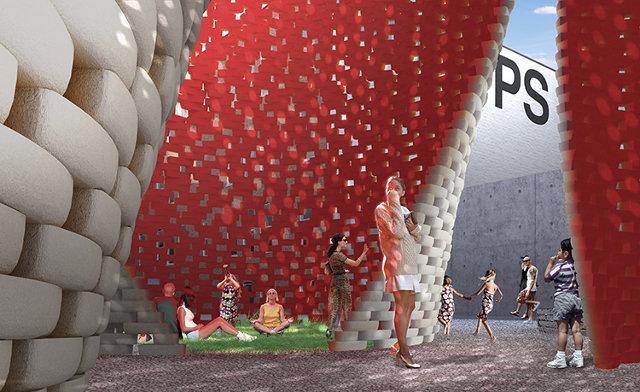

This summer, a new kind of building will sprout amid New York City’s garden of glass and steel. Using bricks biologically engineered to grow themselves from plant waste and fungal cells, David Benjamin’s Hy-Fi will rise as a giant circular tower that creates a cool micro-climate for pedestrians in searing city heat. Bet you’ve never seen a brownstone do that before.

Hy-Fi was selected by the art museum MoMA PS1 as the winner of its Young Architects Program for 2014. The prize: Constructing the building in the museum courtyard, starting this June. But Hy-Fi is more than just an art piece. It could also present a radical alternative to building up our city’s future--one that’s inspired by biology, stretched even further by human technology, and part of a zero-waste, cradle-to-grave cycle.

Instead of mining sandstone or carting in metal by truck, all of Hy-Fi’s prep work will take place on-site, explains Benjamin, principal architect at The Living and director of Columbia University’s Living Architecture Lab. The bricks, produced by the startup Ecovative, are grown from mycelium, or mushroom cells that grow upwards and outwards like a branch. Combined with agricultural waste like corn stalks, the materials fuse and shape into a solid brick--or into whatever shape the architect wants.

“It’s really inexpensive, almost cheaper than anything,” Benjamin says. “It emits no carbon, it requires almost zero energy, and it doesn’t create any waste--in fact it almost absorbs waste. We think that’s a pretty new and pretty revolutionary way of making building materials.”

“It’s our interest and our belief that a single building, a single piece of architecture, can’t and shouldn’t be considered alone,” Benjamin says. “When that building comes down, those materials need to go somewhere. The building interacts with the forces of wind and water. The building consumes energy. The building interacts with people and culture and society.”

But the building’s a hybrid--it’s part-synthetic, too. Hy-Fi will also feature a material designed by 3M, the manufacturer of Post-Its and Scotch Tape, to make some of the bricks at the top of the structure reflective. Some of the brick molds, or plastic trays, will also act like mirrors that grab sunlight from the top of the structure and bounce it down into the low, cool, dark spaces at the bottom.

Hi-Fy also inverts the way typical brick buildings work. Instead of having heavier materials at the bottom, Hi-Fy draws in cool air at the base, which is more porous, then pushes hot air out the top, similar to how a heart muscle pumps blood.

At the end of the installation, the local nonprofit Build It Green will help compost the building and put the materials to use as fertilizer.

To Benjamin, the building represents a fusion of natural systems and human ingenuity, though wherever you draw the line between the two is an ongoing debate. “We’re using some of the most fascinating properties of biological systems, but also extending them, using human technologies to enable new possibilities with them,” Benjamin says. “This is not just a return to nature, but a hyper nature.”

A new kind of building is set to sprout amid New York City’s garden of glass and steel.

Using bricks biologically engineered to grow themselves from plant waste and fungal cells, David Benjamin’s Hy-Fi will rise as a giant circular tower.

It will help create a cool micro-climate for pedestrians in searing city heat.

Hy-Fi was selected by MoMA PS1 as the winner of its Young Architects Program for 2014

It could also present a radical alternative to building up our city’s future.

Made from organic material that can be turned into fertilizer, this installation will show off a radical, zero-waste building technology that could help chill down sweltering city streets.

This summer, a new kind of building will sprout amid New York City’s garden of glass and steel. Using bricks biologically engineered to grow themselves from plant waste and fungal cells, David Benjamin’s Hy-Fi will rise as a giant circular tower that creates a cool micro-climate for pedestrians in searing city heat. Bet you’ve never seen a brownstone do that before.

Hy-Fi was selected by the art museum MoMA PS1 as the winner of its Young Architects Program for 2014. The prize: Constructing the building in the museum courtyard, starting this June. But Hy-Fi is more than just an art piece. It could also present a radical alternative to building up our city’s future--one that’s inspired by biology, stretched even further by human technology, and part of a zero-waste, cradle-to-grave cycle.

Mushroom Bricks Photo: Ecovative

Instead of mining sandstone or carting in metal by truck, all of Hy-Fi’s prep work will take place on-site, explains Benjamin, principal architect at The Living and director of Columbia University’s Living Architecture Lab. The bricks, produced by the startup Ecovative, are grown from mycelium, or mushroom cells that grow upwards and outwards like a branch. Combined with agricultural waste like corn stalks, the materials fuse and shape into a solid brick--or into whatever shape the architect wants.

“It’s really inexpensive, almost cheaper than anything,” Benjamin says. “It emits no carbon, it requires almost zero energy, and it doesn’t create any waste--in fact it almost absorbs waste. We think that’s a pretty new and pretty revolutionary way of making building materials.”

If Hy-Fi is the way of the future, it looks very different from many of the stark, Jetsons-like visions we often see. But Benjamin is convinced that biology can teach us how to build structures that are more than just resilient--he believes nature can show us how to make materials that actually perform better under stress. Buildings, he believes, are just as much a part of the larger ecosystem as flora and fauna.

“It’s our interest and our belief that a single building, a single piece of architecture, can’t and shouldn’t be considered alone,” Benjamin says. “When that building comes down, those materials need to go somewhere. The building interacts with the forces of wind and water. The building consumes energy. The building interacts with people and culture and society.”

But the building’s a hybrid--it’s part-synthetic, too. Hy-Fi will also feature a material designed by 3M, the manufacturer of Post-Its and Scotch Tape, to make some of the bricks at the top of the structure reflective. Some of the brick molds, or plastic trays, will also act like mirrors that grab sunlight from the top of the structure and bounce it down into the low, cool, dark spaces at the bottom.

Hi-Fy also inverts the way typical brick buildings work. Instead of having heavier materials at the bottom, Hi-Fy draws in cool air at the base, which is more porous, then pushes hot air out the top, similar to how a heart muscle pumps blood.

At the end of the installation, the local nonprofit Build It Green will help compost the building and put the materials to use as fertilizer.

To Benjamin, the building represents a fusion of natural systems and human ingenuity, though wherever you draw the line between the two is an ongoing debate. “We’re using some of the most fascinating properties of biological systems, but also extending them, using human technologies to enable new possibilities with them,” Benjamin says. “This is not just a return to nature, but a hyper nature.”

Comments

Post a Comment