ORIGINAL: City Lab

Eric Jaffe @e_jaffe

Feb 20, 2015

New research suggests the social benefits of dense urban areas might follow timeless rules.

Productivity was greater in large ancient cities, just as it is in dense urban areas today (above, ruins in Teotihuacan). (Wiki Commons)

The more scientists study urban development, the more they realize that cities are like nothing else in nature. The social interactions that occur in a dense setting have a multiplier effect: they create more wealth, greater ideas, and larger buildings, though they can also spread more disease. At a certain point, in ways good and bad, city life adds up to far more than the sum of individual city lives.

The Santa Fe Institute, and its roster of scientists including Geoffrey West and Luis Bettencourt, has been home to many of these insights. These researchers are now able to predict various socioeconomic benefits, such as GDP or road infrastructure, with startling accuracy based on just a city's population. Urban life, it turns out, conforms surprisingly well to mathematical equations.

"What I realized was the parameters they were discussing as potentially explaining these patterns were not something that was unique to contemporary capitalist, democratic, industrialized nations," says Ortman, who's now at the University of Colorado at Boulder. "They're much more basic properties of presumably any human society anywhere." "There's a reason why the human population is rapidly urbanizing today. There really are intrinsic advantages to larger scales of social organization."

In a paper released today in Science Advances, Ortman and collaborators (including Bettencourt) report what they call "striking and exciting" new evidence supporting just that hunch. The researchers report that productivity was greater in large ancient cities just as it is in dense urban areas today—though the nature of that production was monument and building size, rather than modern economic measures like GDP.

The work supports the basic idea of cities as great "social reactors." In dense places, communal assets set in close proximity (such as food gathering or transport networks) free up people to direct energy in more beneficial directions (such as labor coordination or knowledge specialization). Highly dispersed places, where social connections are farther apart, don't reap the same productivity gains.

"One thing that really strikes me is that this research suggests that humans—human groups—do generally benefit from coordinating their behavior at larger scales," says Ortman. "In a sense, there's a reason why the human population is rapidly urbanizing today. This work suggests that overall there really are intrinsic advantages to larger scales of social organization."

Bigger Cities Build Bigger Civic Monuments

The researchers drew their conclusions from a close analysis of archaeological survey data on about 4,000 pre-Hispanic settlements in the Basin of Mexico that date from ancient times through the end of the Aztec era in the 16th century. Among other things, the surveys documented the size, shape, and general measures of all sorts of buildings from these settlements. These included the likes of civic monuments as well as individual homes.

Such details gave Ortman and collaborators an impressive window into urban life from much earlier times. They first looked specifically at the size and volume of monuments in these settlements, with the idea that such buildings reflect productivity of a city—a sort of ancient proxy to modern GDP. If social interactions truly enhanced urban life in a universal way, they would expect to see monument size increase with city size, just as GDP does in urban areas today.

"What [the results] do suggest is that essentially there is a functional reason why urbanization in general improves the overall material well-being of humanity," says Ortman. "It reduces the amount of resources needed per person and it increases the amount that's produced per person."

And Bigger Individual Homes, Too

The researchers also analyzed individual home sizes, using archaeological data on floor areas of palaces as well as more ordinary houses. They reasoned that as people in these settlements accumulated more material wealth, they also likely acquired additional possessions, which in turn would lead them to build bigger residences. Just as monument size served as a proxy for social productivity, home size was a proxy for personal productivity.

Domestic home area (solid) outpaced population growth (dotted), too. (Science Advances)

"These settlements of the Aztecs, which is the last civilization of this period we're studying, seem to express similar things to what we see in modern cities," says Bettencourt. "Even though they're about what these societies did, like building monuments and houses, rather than putting money in the bank."

That's not to say this increased wealth was distributed evenly. The researchers found the top 10 percent of households made up 40 to 50 percent of the housing area—a statistic they call comparable to levels of income disparity found in the United States today. Ortman says that finding raises the question of whether or not it's really possible to develop a big-scale urban society that shares household wealth equally.

"It doesn't look like ancient Mexico figured out how to accomplish that," he says.

The Digital Age Won't Change Things—Yet

Bettencourt says he's encouraged that social networks in different times and spaces organized themselves according to some general patterns. But despite these continuities, he stops short of concluding that all cities have operated the same way across all ages. He'd still like to see how things played out in other systems—especially in places where people produced their own food. "When we have the ability to send food via WiFi, or send calories via fiber optic cable, then we'll really be in a new world."

He suspects researchers will find a continuum of urban development based on how (and to what degree) cities provide residents with food, either through markets or central authority. Once food gathering is organized in a collective manner, he says, individuals no longer have to devote as much energy to obtaining it. Cities that take this step seem to cross an important threshold toward the creation of denser environments that facilitate productivity gains.

"We're trying to understand some of these interesting patterns of potentially different kinds of urbanism that happened throughout history," he says.

Another big question raised by this line of research is when—or whether—digital social networks will change the way cities develop in the future. Ortman doubts we'll see much of a shift so long as food needs to be physically transported into a city, and into a home, and into a mouth. Until then, he says, distance will remain a limiting factor in what people can accomplish in a given day.

"When we have the ability to send food via WiFi, or send calories via fiber optic cable, then we'll really be in a new world," he says.

*CORRECTION: An earlier version of this post included an image of the Aztec Ruins in New Mexico, not a settlement in the pre-Hispanic Basin of Mexico.

Eric Jaffe @e_jaffe

Feb 20, 2015

New research suggests the social benefits of dense urban areas might follow timeless rules.

Productivity was greater in large ancient cities, just as it is in dense urban areas today (above, ruins in Teotihuacan). (Wiki Commons)

The more scientists study urban development, the more they realize that cities are like nothing else in nature. The social interactions that occur in a dense setting have a multiplier effect: they create more wealth, greater ideas, and larger buildings, though they can also spread more disease. At a certain point, in ways good and bad, city life adds up to far more than the sum of individual city lives.

The Santa Fe Institute, and its roster of scientists including Geoffrey West and Luis Bettencourt, has been home to many of these insights. These researchers are now able to predict various socioeconomic benefits, such as GDP or road infrastructure, with startling accuracy based on just a city's population. Urban life, it turns out, conforms surprisingly well to mathematical equations.

As a postdoctoral researcher at the institute, anthropologist Scott Ortman recalls thinking that the social patterns displayed by contemporary cities didn't seem much different from how some older civilizations behaved. He began to wonder if the principles that governed these patterns were fundamentally the same across times or places.

"What I realized was the parameters they were discussing as potentially explaining these patterns were not something that was unique to contemporary capitalist, democratic, industrialized nations," says Ortman, who's now at the University of Colorado at Boulder. "They're much more basic properties of presumably any human society anywhere." "There's a reason why the human population is rapidly urbanizing today. There really are intrinsic advantages to larger scales of social organization."

In a paper released today in Science Advances, Ortman and collaborators (including Bettencourt) report what they call "striking and exciting" new evidence supporting just that hunch. The researchers report that productivity was greater in large ancient cities just as it is in dense urban areas today—though the nature of that production was monument and building size, rather than modern economic measures like GDP.

The work supports the basic idea of cities as great "social reactors." In dense places, communal assets set in close proximity (such as food gathering or transport networks) free up people to direct energy in more beneficial directions (such as labor coordination or knowledge specialization). Highly dispersed places, where social connections are farther apart, don't reap the same productivity gains.

"One thing that really strikes me is that this research suggests that humans—human groups—do generally benefit from coordinating their behavior at larger scales," says Ortman. "In a sense, there's a reason why the human population is rapidly urbanizing today. This work suggests that overall there really are intrinsic advantages to larger scales of social organization."

Bigger Cities Build Bigger Civic Monuments

The researchers drew their conclusions from a close analysis of archaeological survey data on about 4,000 pre-Hispanic settlements in the Basin of Mexico that date from ancient times through the end of the Aztec era in the 16th century. Among other things, the surveys documented the size, shape, and general measures of all sorts of buildings from these settlements. These included the likes of civic monuments as well as individual homes.

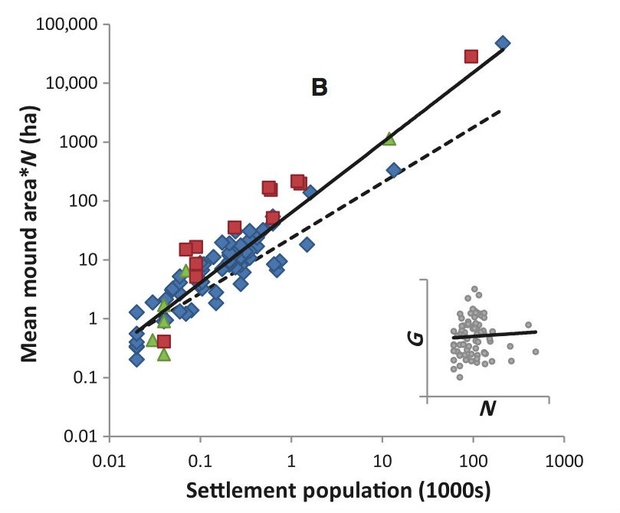

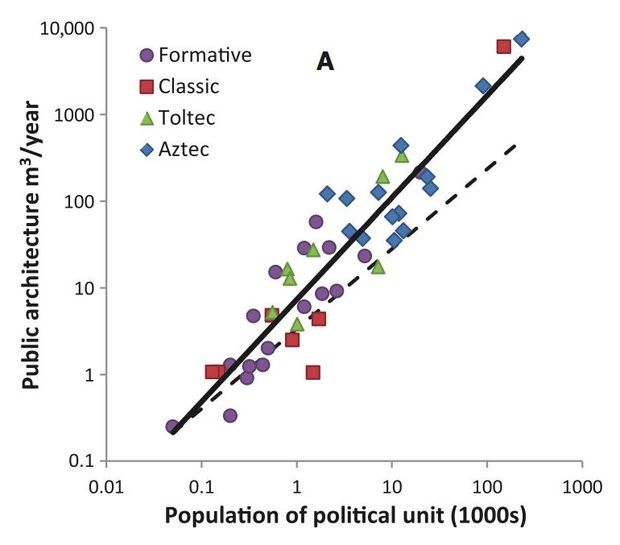

Such details gave Ortman and collaborators an impressive window into urban life from much earlier times. They first looked specifically at the size and volume of monuments in these settlements, with the idea that such buildings reflect productivity of a city—a sort of ancient proxy to modern GDP. If social interactions truly enhanced urban life in a universal way, they would expect to see monument size increase with city size, just as GDP does in urban areas today.

Indeed, they found just that. The chart below shows that monument size (the solid line) grew at a "super-linear scale" in big cities—in other words, faster than the population growth rate (the dotted line). Larger groups of urban laborers built bigger monuments than smaller groups, and built them faster. The researchers attribute the boost in productivity to the collective power of social networks in these cities, given the limited technological advances identified over this period.

Monument construction rates (solid line) outpaced population growth (dotted line) in large ancient cities (Science Advances)

Monument construction rates (solid line) outpaced population growth (dotted line) in large ancient cities (Science Advances)

Monument construction rates (solid line) outpaced population growth (dotted line) in large ancient cities (Science Advances)

Monument construction rates (solid line) outpaced population growth (dotted line) in large ancient cities (Science Advances)"What [the results] do suggest is that essentially there is a functional reason why urbanization in general improves the overall material well-being of humanity," says Ortman. "It reduces the amount of resources needed per person and it increases the amount that's produced per person."

And Bigger Individual Homes, Too

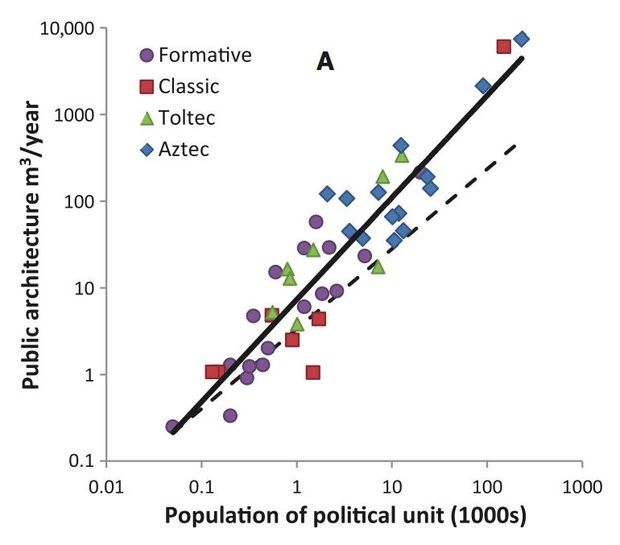

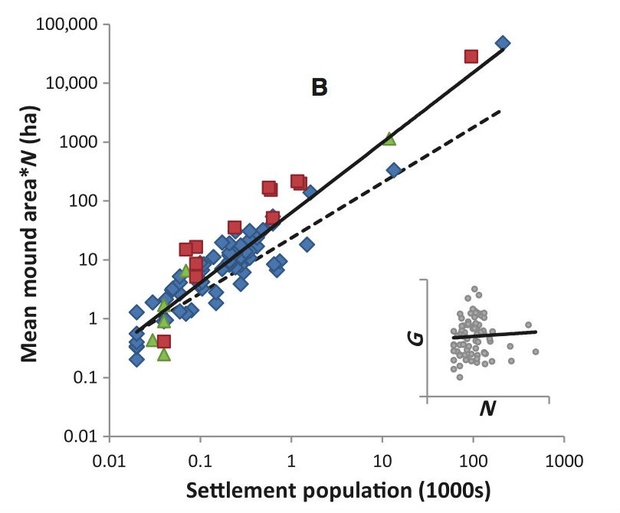

The researchers also analyzed individual home sizes, using archaeological data on floor areas of palaces as well as more ordinary houses. They reasoned that as people in these settlements accumulated more material wealth, they also likely acquired additional possessions, which in turn would lead them to build bigger residences. Just as monument size served as a proxy for social productivity, home size was a proxy for personal productivity.

Once again, as the chart below shows, they found evidence of super-linear scaling in big cities. Individual homes were larger, on average, in cities that were more populated—suggesting that urban social networks multiply productivity (and thus wealth) at a personal level, too. By aggregating in one dense place, these ancient people were able to "balance the costs of moving within the settlement with the benefits of the resulting social interactions," just as efficient big cities do today.

Domestic home area (solid) outpaced population growth (dotted), too. (Science Advances)

"These settlements of the Aztecs, which is the last civilization of this period we're studying, seem to express similar things to what we see in modern cities," says Bettencourt. "Even though they're about what these societies did, like building monuments and houses, rather than putting money in the bank."

That's not to say this increased wealth was distributed evenly. The researchers found the top 10 percent of households made up 40 to 50 percent of the housing area—a statistic they call comparable to levels of income disparity found in the United States today. Ortman says that finding raises the question of whether or not it's really possible to develop a big-scale urban society that shares household wealth equally.

"It doesn't look like ancient Mexico figured out how to accomplish that," he says.

The Digital Age Won't Change Things—Yet

Bettencourt says he's encouraged that social networks in different times and spaces organized themselves according to some general patterns. But despite these continuities, he stops short of concluding that all cities have operated the same way across all ages. He'd still like to see how things played out in other systems—especially in places where people produced their own food. "When we have the ability to send food via WiFi, or send calories via fiber optic cable, then we'll really be in a new world."

He suspects researchers will find a continuum of urban development based on how (and to what degree) cities provide residents with food, either through markets or central authority. Once food gathering is organized in a collective manner, he says, individuals no longer have to devote as much energy to obtaining it. Cities that take this step seem to cross an important threshold toward the creation of denser environments that facilitate productivity gains.

"We're trying to understand some of these interesting patterns of potentially different kinds of urbanism that happened throughout history," he says.

Another big question raised by this line of research is when—or whether—digital social networks will change the way cities develop in the future. Ortman doubts we'll see much of a shift so long as food needs to be physically transported into a city, and into a home, and into a mouth. Until then, he says, distance will remain a limiting factor in what people can accomplish in a given day.

"When we have the ability to send food via WiFi, or send calories via fiber optic cable, then we'll really be in a new world," he says.

*CORRECTION: An earlier version of this post included an image of the Aztec Ruins in New Mexico, not a settlement in the pre-Hispanic Basin of Mexico.

Comments

Post a Comment